Serving time on the fire line

The successes and failures of Oregon’s 72-year-old incarcerated wildland firefighting program are highlighted by the experiences of former participants.

By BERIT THORSON | University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication

Terminal Project (Unpublished)

Completed June 18, 2023

Nathan Mosley (right column, middle) with his crew on a fire near Medford, Oregon, in 2022. Nathan Mosley/Contributed Photo

On a mountainside in Oregon’s Tillamook State Forest, in the pitch black, lying in a hole he’d dug into the ground, Nathan Mosley looked at the stars. He was completely alone. His body relaxed. There was no work to be done; it was a waiting game now.

Mosley’s fire suppression crew had the night shift and were simply extinguishing flareups as they came. Right now, they could take a break and enjoy being in nature, away from the reality of their lives off the mountain.

Mosley was about six-and-a-half years into a 10-year sentence in Oregon’s prison system. One of about 300 incarcerated people trained as a wildland firefighter, he felt almost free, lying in that hole in the ground on the side of a mountain.

At South Fork Camp, the unfenced, minimum-security prison where Mosley was housed, he could see the stars, but the lights of the prison polluted their brightness. It was only out on a night fire, away from security lights and curfews, when it was just him and the stars, that he felt peace. He felt not like a prisoner or an addict or a father away from his son, but a person. “Yeah, that's the fun stuff,” he mused, remembering that clear night. “It gets you out of your head about being in prison and being a slave firefighter or a slave worker and dealing with crappy food and arrogant, disrespectful guards.” He could just focus on the stars — a luxury for someone who must avoid making a mistake, something that could mean losing that day’s earnings.

Firefighters monitoring fire as it spreads toward a dozer line at the Double Creek fire on September 3, 2022. Payton Bruni/Contributed Photo

For all the calm of that night on the mountain, putting out a wildfire is hard work. Crew members cut down brush and trees, trying to remove potential kindling for the fire. They dig containment lines in the soil to stop the fire’s progress just a few feet away from flames taller than some people.

On one fire, Mosley’s crew boss took a wrong turn while driving to the staging area where they would receive their location assignment. Mosley and his crew found themselves surrounded by fire on all four sides of the truck. Heat radiated in through the windows. Fire was all he could see. It felt apocalyptic, he said, like “hellfire and brimstone.”

Somehow, they navigated out of the fire and found the staging area. Mosley, 40, relied on his training. He followed instructions, listening to the voices yelling above the commotion as he dug the containment line just a few feet away from intense flames, side-by-side with people who hourly earned more than double the $9.72 he received per day.

The hill above was engulfed in fire as far as he could see. He watched for raining embers and wore his bandana over his mouth, attempting to keep the cleaner air in and the soot and ash out. The smell permeated everything. Fires away from structures, like this one, smell like a campfire. Fires that burn through structures, equipment or cars, Mosley said, smell noxious.

***

Chris Murphy, another incarcerated wildland firefighter, distinctly recalls the chaos of what he considers his first real experience of fire. It was just before the 2020 Labor Day fires began. He remembers the crew boss telling them to stay where they were — hold the line — and that the fire was coming their way. One of probably 100 firefighters from 10 different crews, standing in a line with 20 feet between each person, Murphy’s body began to thrum. “You just hear what sounds like thunder — not even thunder,” he said, “just a whole-body vibration of sound coming.” He realized it was a wall of fire heading toward him.

Helicopters circled overhead, carrying people with strobe lights deciding where to drop water. The heat was suffocating. It made him feel sick. Dust was getting into his throat. When he was desperate, he put his mouth next to the hose’s nozzle because right next to it was the only place without smoke, where there was clean air. When he occasionally had to use water instead of dirt to smother the fire, it instantly turned to steam and burned any uncovered skin. Everyone was screaming to move faster, faster, calling out where to go and when.

He could hear the chainsaws cutting down trees and brush, the shovels and Pulaskis — a tool used to both chop wood and break soil — digging into the dirt to reinforce the containment line. He could feel the weight of three gallons of water in his pack. He was going as quick as he could, while still methodically doing tasks as he’d been trained so he wouldn’t cause problems for himself or his crew later. He worried a tree would fall on him, even with someone assigned specifically to look out for that particular danger.

“Literally everything around us was on fire,” Murphy, 34, said. Despite the chaos, he said, “You feel alive, almost. I don’t know how to describe it. It was amazing. I loved it.”

Still, the work exhausted him. He left fires with ash in his ears, what felt like an adult version of a child with sand in their ears after a day at the beach. His nose had soot in it. It can take weeks for tissues and Q-tips to stop coming away black after a fire.

There is nothing like the terror of fighting wildfires. There’s also nothing like the adrenaline Murphy felt, the natural high that came from putting his life on the line and battling nature. At some point, the training kicks in and the process feels more natural.

Navigating questionable incentives

Murphy, Mosley, and another former incarcerated firefighter, Adam Gregg, all describe how hard they worked. But what they did wasn’t for the Oregon Department of Corrections (DOC), at least not emotionally. They worked for their crew boss, their fellow crew members, the people whose communities they protected, their own desire to atone for their choices. But not for the DOC. Not for an entity that sometimes didn’t ensure they had a day off from hard manual labor. Not for the institution that profits off its fire contracts with the Department of Forestry while paying the people it claims to support and rehabilitate next to nothing. They all felt disposable, exploited. They felt like slave labor.

At the same time, all three are glad to have done it. They enjoyed the work and wouldn’t want the fire program to not exist. It helped them to reintegrate into their communities. But they also aren’t the ones receiving the main benefits of their work — that’s the Department of Corrections and Oregon residents. Their labor means less state money spent employing private contractors for the unglamorous, intense mop-up work that happens after a fire is mostly out, which is what incarcerated firefighters are usually doing during the fire season. The dichotomy between what the program claims to do and what participants actually experience is complicated and not quickly bridged, so it can be easy to gloss over. In the end, the program is simultaneously beneficial and exploitative.

Oregon Department of Corrections claims to ensure the program is voluntary. Thomas McLay, managerial overseer of the Wildland Fire Program, said participants can leave it whenever they want to. Further, program recruitment itself is simple, McLay said. They don’t push people to participate. “We make them aware of [the opportunity] and they fill out the application,” he explained.

On top of the ethical tensions of the fire program are important semantics. People who are incarcerated in Oregon’s prisons have been called adults in custody — AICs — since January of 2020 by the Department of Corrections. According to the department, the phrase recognizes their humanity more than calling them inmates or convicts. The Marshall Project surveyed formerly incarcerated people about what words they prefer and found that person-focused language, like someone who is incarcerated, was favored. While adult in custody may be better than inmate, the abbreviation AIC especially seems to undermine the point of using person-focused language like adult in custody. AIC becomes another way of separating incarcerated people from their individuality and humanity. Words matter, and those words help to define people’s experiences and perspectives.

There are seven criteria people must meet to be eligible for the fire program, including that they must be housed in a minimum-security facility, within five years of release, and cleared to go on work crews outside of prison. In addition, incarcerated people must be cleared by medical and behavioral health services, receive approval from their counselor and have a good conduct history from the institutions where they’ve been incarcerated. And, not surprisingly, they cannot be convicted of sex offense crimes or arson.

Wildland fire engines lined up at the Double Creek fire on September 2, 2022. Payton Bruni/Contributed Photo

A maximum of 25 suppression crews of 10 people each are contracted by the Oregon Department of Forestry each year, said Nathan Cantlin, the Department of Corrections’s operations program manager. That way, firefighting does not impede on the work incarcerated people do to keep their facilities running. Such work includes more typical prison jobs seen in movies and TV shows, like working in the library or on laundry or kitchen duty.

Toward the end of his sentence, Mosley worked in the woodshop, helping to make the wooden signs seen around the state on hiking trails and in national forests and state parks. According to the Department of Corrections, in October 2022, there were 12,299 total adults in Oregon’s prisons. In 2020, researchers at the University of Oregon found that the DOC deployed 288 people across 37 fires, about 2% of the state’s total prison population.

***

The crews work up to two weeks on a fire, with the possibility to extend to three weeks if their support is needed. After completing a deployment, said Cantlin and McLay, the incarcerated firefighters are required to take two days off when they return to the prison where they are housed. There, they can rest and contact family or friends, as they don’t have a way to communicate with anyone while they’re deployed to a fire.

Realistically, that is not what happens. Mosley said he was dispatched for about 28 days straight during the 2020 Labor Day fires. Because he conducted normal forestry work on some days, the monthlong stretch didn’t meet the requirements for time off. For two weeks, his crew conducted their normal reforestation work during the week and then spent three days over the weekend on call for fires. On the third Monday — day 15 — around 4 a.m., his crew was deployed, working 12- to 16-hour shifts for seven or eight days. The day after that finished, they deployed to another fire for an additional six or seven days.

Although he was on standby for six days that month, Mosley never truly had a day off. He didn’t have access to phones while on standby, just as he didn’t while working the fires. And, like all people incarcerated in Oregon, he could only earn a maximum of $82 per month.

Chart and data provided by Leigh Johnson, a professor and researcher at the University of Oregon.

In 2020, the Department of Corrections earned $936,977 from the work of incarcerated firefighters and correctional officers supervising the crews on wildland fires, according to data from public records requests compiled and evaluated by researchers with the University of Oregon.

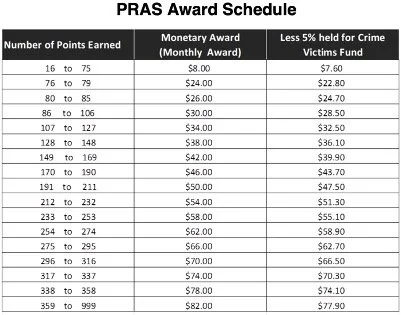

Everyone incarcerated in Oregon earns monetary awards, not wages. This distinction is important because the monetary awards are not necessarily a consistent amount, and the AICs aren’t categorized as employees. They can earn from 4–18 points per day, depending on the work they are doing.

At the end of each month, the daily points each person has earned are totaled and then converted to a monetary award, 5% of which is held for a crime victims assistance fund. The points correlate to monetary awards ranging from $8 to $82 for the month, which becomes $7.60 to $77.90 after 5% is taken. Additionally, Gregg said, 10% more may be deducted to pay court-ordered restitution, fees, or fines that many people owe.

“Wildland fire crews are typically the highest point value assignments in the state,” said Cantlin. They earn 17 points per day while working on a fire. Cantlin said it’s rare to earn 18 points and that the scale they use is not made by the Department of Corrections.

Unlike some positions, wildland firefighters receive supplementary compensation. The Department of Forestry gives fire crew members “$6 per day on top of [their 17 points] as an additional award,” Cantlin said.

“I mean, $6 a day sounds like a f—ing joke, but when you’re used to making a dollar a day,” Gregg said, “that’s actually quite a bit of money.”

Incarcerated firefighters do not have any say in the hours they work or the fires they combat. The Department of Forestry puts in a resource order with the Department of Corrections, which then evaluates what crew would be best to send and from which prison.

Performance Recognition and Awards System (PRAS) chart provided by Amber Campbell with the Oregon DOC.

If an incarcerated firefighter works the maximum 22 days on a fire — which rarely happens — they could receive up to $214 in a month between their monthly award and their extra $6 a day. That breaks down to $9.72 per day or 81 cents per hour. Comparatively, entry-level civilian firefighters at private firefighting contractor Grayback Forestry earn about $20 per hour.

In addition to the other benefits they receive, incarcerated crews get catered food on fires. Although he suspects civilian crews dislike that same food, Gregg said, “The type of food that we would get [on a fire site] is — you know, I can’t even describe how much better it is than the food that you would get in prison. So that alone is a huge motivation.”

Furthermore, participants enjoy a little more freedom while out on fires — like looking at the stars in the middle of the night or taking a walk during a slow day’s lunch break — because they are in the custody of the Department of Forestry crew bosses who can be more lenient than their guards. Plus, they sometimes get to travel to different parts of the state.

“What I would say in contrast to all those great things about fighting fire is that the alternative is you sit in a cage,” Gregg said. “So, while it may sound voluntary because I really wanted to do it, I would say that in contrast to the alternative, it’s not really voluntary.”

Training for danger

Prisoners have been used to fight fires throughout history. In 1910, the mayor of Wallace, Idaho, commanded their jailed men “to form a human fire line” on the street to protect its buildings as a massive wildfire burned toward his town, writes author Timothy Egan in “The Big Burn.” In Oregon, an official, organized version of this practice has existed since 1951 when a labor program began at South Fork, more than 70 years ago.

The incarcerated crews are trained by the Oregon Department of Forestry, mostly at the jointly operated South Fork Camp, located about 45 miles west of Portland. Today, most participants in the Department of Corrections’s wildland fire program are housed there, said Cantlin. While South Fork hosts the bulk of the crews, there are participating facilities throughout the state.

Adults in custody take the same classes that wildland firefighters do on the outside, said Cantlin. Prior to deployment, they receive training that is specific to their role: kitchen, camp or fire crew. Fire suppression crews complete the same basic required trainings and safety courses as civilian crews. Some participants are also trained to use chainsaws.

South Fork Forest Camp was established in 1951 as a jointly operated facility between the Oregon Department of Forestry and the Oregon Department of Corrections.

All program participants learn first aid and CPR, and those serving on camp or kitchen support crews must have a food handler safety card, all of which is included in the training provided by the Department of Forestry. Cantlin said every person, regardless of crew assignment, must also be able to walk three miles with a 45-pound pack in under 45 minutes, just like any civilian wildland firefighter.

Once they complete the training, the AICs are certified in wildland firefighting, the Department of Corrections claims, although they don’t receive the red card that civilian firefighters can present to prove their training. Cantlin said their experience can help them find jobs on civilian crews after release. Dale Lee, who works at private wildland firefighting contractor Grayback Forestry, said people who leave the DOC have as good a chance as civilians to join their crews, but it doesn’t happen all that often.

With all the training they endure and experience they gain, it’s true that incarcerated firefighters can work on a civilian crew after release. But it’s not as practical a possibility for many of the people leaving the program as Cantlin and other DOC officials make it seem. Probation officers told Mosley and Murphy not to join private crews while they were on probation because they would have to leave the state for work, which complicates things. So, upon release, they would need to find other jobs and wait until they were no longer “on paper” to join a crew. But by that time, they would have become more established in their new lives and routines.

***

Firefighting is both a technical and physical job. It requires a clear understanding of protocol and chain of command as well as knowledge of fire behavior and the capability to endure the physical demands. Chris Murphy carried two or three gallons of water at all times, which is about 24 pounds. He also wore his helmet and Nomex fire-resistant uniform and carried tools, food, a fire shelter, and shared gear like a hose or chainsaw.

One time, Murphy’s crew was assigned to the night shift. To get to their destination, they climbed hand over hand up three-inch fire hoses that were tied around trees and hanging down the mountainside, which was “damn near straight up and down.” Murphy kicked his boots into the dirt, trying to create makeshift stairs to help his journey. Because he would be in the middle of nowhere overnight, he figured it would be cold, so he dressed warmly. Underneath his gear were his long johns, which he had sweated through long before reaching camp as he stumbled around in the dark while making his way up the mountain. Once he stopped climbing, the sweat froze, and the cold set in.

Murphy wasn’t supposed to carry a blanket due to the extra weight, so when he had a break, he’d gather warm coals and bury them just underground. He rested on top of them like a bed for warmth.

Beyond extreme temperatures and weather, firefighters face bodily danger, too. Murphy said he worried about putting his body on the line for the Department of Corrections when he’d seen people’s medical conditions, from torn ligaments to poison oak, go untreated. Safety became Gregg’s top priority during his first season when a civilian firefighter died from a falling tree. He thought it would be a tragedy to die while in prison doing a dangerous job for which he was barely paid.

Still, officials and program participants alike say the program offers an opportunity for incarcerated people to give back to their communities and be proud of the work they’re doing. It helps prepare them to reintegrate into society, since only people who are within five years of release can participate. Sometimes, it offers them a feeling they never imagined they’d experience.

Adam Gregg (third from right) with his crew at the 2020 Echo Mountain fire in Otis. Adam Gregg/Contributed Photo

Protecting Otis

It had been nearly two weeks since the small town of Otis, Oregon, was first set aflame by the Echo Mountain Complex Fire, one of the devastating 2020 Labor Day fires. Adam Gregg remembers their crew had been first to the scene. After days of exhausting work, the fire was smoldering, and residents were beginning to return.

It was the first time Gregg had protected people’s homes. Normally, incarcerated crews are deployed to fires in the middle of nowhere, doing mop-up work, which consists of ensuring a fire is fully out. But in 2020, civilian crews couldn’t manage all the wildfires threatening towns alone. The fire that descended upon Otis was really the first time Gregg would see how people feel about incarcerated firefighters being entrusted with their homes.

When residents returned, it felt like it happened all at once. There was a line of cars slowly making its way through the town. People made signs, thanking the firefighters.

“They were honking their horns, going crazy,” Gregg, 36, said, a lightness and incredulity in his voice, even after two years had passed. “I can't even — it was like being a rockstar. We were heroes.”

He felt a surge of pride as one man offered to have the whole crew over to his house for dinner after they were each released. Gregg knew all the effort that had gone into saving the man’s house. He felt lucky to experience that kind of appreciation. People’s gratitude was palpable, despite the destruction of some of the houses in Otis.

Adam Gregg (second from left) and Chris Murphy (right) with fellow crew members during the 2020 fire season. Adam Gregg/Contributed Photo

Mosley was on a different crew at the same fire, receiving similar praise but feeling undeserving. His crew came in toward the end of the fire from another assignment. By the time he arrived in Otis, the fire had done most of its damage. He saw charred tricycles next to incinerated houses. Not all the homes were gone — he thinks maybe every fifth home he passed was still standing — but he’d had little to do with saving any of them.

Mosley and his crew helped with the last bit of suppression but had missed most of the work done to protect structures. When people returned to town and thanked him for saving their homes, although he appreciated the recognition and thanks, he felt like an imposter.

“We were just there cleaning up and all these people expressed this just intense gratitude for us being there,” Mosley said. He remembers “feeling like we didn't really do anything” for that fire. Still, he felt proud of the work he was doing and how he was serving the community. He liked that people didn’t seem to care he was incarcerated.

Recognizing a workforce we cannot do without

Leigh Johnson, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Oregon whose research focuses on disasters and climate risk, worries that narratives about incarcerated labor often fail to recognize the true beneficiaries of such labor: the state and taxpayers, since incarcerated firefighters are much cheaper than civilian ones.

When wildfires rage, the prison population is an integral part of fire suppression. Oregon has even written incarcerated firefighters into its emergency management response documents.

Adam Gregg (second from left) and Chris Murphy (right) with fellow crew members during the 2020 fire season.

“I think one of the big messages of our project is all of the very ordinary and kind of day-to-day ways in which these prisoner crews are essential that go far beyond what we often think of around mega-fires,” Johnson explained.

Yes, she said, incarcerated crews are saving homes and doing the more desirable, visible work during mega-fires like the Echo Mountain Complex Fire in Otis. But most of the time, they’re fighting fires in the middle of nowhere that no one hears about or doing mop-up work consisting of intense physical labor like chopping down burnt trees and removing burning debris from near the containment line.

Firefighters lighting vegetation on fire during a backburn operation at the Double Creek fire on September 4, 2022. Payton Bruni/Contributed Photo

“[Incarcerated firefighters] get stuck with the really backbreaking mop-up work,” Johnson said. “So, [they are] absolutely essential. And at this point, given the way that the state approaches fire suppression, no, I don’t think we could do without them.”

As climate change worsens and wildfires become more intense and prevalent in new areas, Johnson expects the role of incarcerated crews to grow “increasingly significant.” Wildfires in Oregon are a smoky staple of the summertime, and researchers expect their devastating effects to continue. This may mean more experience for program participants to point to after release and more opportunities to serve their community, but it would also mean more work for people who still earn less than Oregon’s minimum hourly wage for a full day’s work doing a job they might not have had full autonomy in choosing.

Reflecting on the experience

Still, Murphy, Gregg and Mosley said they wouldn’t want the program not to exist. Murphy chose South Fork for the firefighting program. He believes fighting fire made him stronger because of its challenges. “[It] definitely made me a more determined person,” he said. “Putting myself through physical things like that made me more confident.”

***

Gregg never planned on being a wildland firefighter, but he did find a lot of meaning from the work he was able to do, especially during the 2020 fire season. “I saved people’s homes. I saved communities. I was, like, a hero — literally, a hero,” he said. “And I’ve never had a job like that. I mean, a lot of people go their whole lives without having that feeling.” Because of his service during that fire season, Gregg’s name was on the list to become one of 41 people whose sentences were commuted — shortened — by Governor Kate Brown in 2021, though he ended up being released a month earlier due to a COVID-related clemency grant from the governor.

Adam Gregg goes through photos from his time as an incarcerated wildland firefighter. Berit Thorson

***

For Mosley, South Fork was a way to give back after taking from society throughout his drug addiction, which led to crime. His motto is: “Prison will change you, no matter who you are. You will never come out the same person you were when you went in. But how you let it change you, you get to decide.”

After his sentence began, Mosley quickly decided to use his time to get clean and make a positive impact. He tutored others working toward degrees, like a high school equivalency diploma, and earned an adult basic education tutoring certificate. Upon transferring to South Fork, he helped set up a GED program for people who don’t have a high school diploma.

Nathan Mosley (second from right) with fellow crew members at a fire near Medford, Oregon, in 2022. Nathan Mosley/Contributed Photo

Nathan Mosley now works for Past Lives LLC, an organization providing opportunities to cultivate trade skills in a workshop and studio space as well as classes. Berit Thorson

He was also drawn to South Fork because his father worked as a structural firefighter, so it seemed fitting. “The idea that I could go fight wildland, I thought was really, really cool and I thought it would really mean something,” he said. “Getting outside of not only myself, but my environment, and trying to be of service to the community.”

Service and acceptance are the foundation of Mosley’s sobriety, for which he celebrated 10 years in March. He wishes people who have never been incarcerated realize that most incarcerated people are more than the choice that led them to prison. “They're people,” he said. “They have feelings, they have emotions, they have family, they have loved ones.” One of the only places he was able to connect to his humanity and identity was on the fire line because the prison system doesn’t leave space for individuality.

***

That night in the Tillamook State Forest, looking at the stars, Mosley felt a sort of peace come over him. He was alone, searching the sky for constellations he no longer knew. It had been more than six years since he’d been anywhere dark enough to see that many stars — so many that it seemed like everything above him was stars.

While fighting three seasons of wildfires and facing feelings of pride, guilt and exploitation, he continually returned to the sky, opening in a giant expanse overhead, to prepare himself for what came next. Now, one year after his release, Mosley still looks to the stars beyond Portland’s city lights to find peace and center himself.