Understanding Oregon’s incarcerated wildland firefighting program

Adults from Oregon’s prisons have been fighting wildfires in the state since 1951. Their work is often overlooked, but it is an essential part of Oregon’s fire response.

By Berit Thorson

November 2022

Written for Reporting II (Fall Term 2022)

Civilian firefighters lighting vegetation on fire during a backburn operation at the Double Creek fire on September 4, 2022. Photo by Payton Bruni.

Adam Gregg, 35, remembers the sky changing from clear blue to pitch black as his crew of firefighters drove through Salem on their way to Otis, where they worked to stop the 2020 Echo Mountain fire from destroying the town.

Although it was his second fire season, Gregg was used to working in the middle of the forest, away from people, not in the center of a neighborhood. Gregg, like the rest of his crew, was incarcerated at the time, only allowed beyond prison walls to protect lives, land and livestock from the wildfires that destroy Oregon’s forests each year.

Most of the time, Oregon’s incarcerated crews fight wildfires that have mostly been put out and are located away from the public. But in 2020, during the historic Labor Day fires, these incarcerated crews were sent to towns like Otis to help protect people’s homes.

“I never understood the amount of power that a wildfire could have until I was there choking on the smoke and seeing the flames,” Gregg recalled. “I think in my mind I always had thought that you could outrun a fire. But that’s not true, actually.”

Oregon has depended on the work of its incarcerated adults to help fight wildfires for over 70 years. However, much of what these crews contribute to Oregon’s wildland firefighting is not part of public discourse as it is done behind the scenes. With the recent passing of Measure 112 in Oregon, which bans slavery or involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime, it’s not clear what will happen with required jobs programs for those in prison, including the wildland firefighting program.

How it started

Oregon’s firefighting program started in 1951 at South Fork Forest Camp in Tillamook, about 70 miles west of Portland. The facility is jointly operated by the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) and the Department of Corrections (DOC).

South Fork Forest Camp is located about 70 miles west of Portland.

Today, most participants in the DOC’s Wildland Fire Program are housed there, at what is now called South Fork Camp, said Nathan Cantlin, DOC’s Operations Program Manager. While South Fork hosts the bulk of the crews, there are participating facilities throughout the state.

Adults in custody (AICs) volunteer for the program, said Thomas McLay, the managerial overseer of the Wildland Fire Program.

Program recruitment is simple, McLay told me. They don’t push AICs to participate. “We make them aware of [the opportunity] and they fill out the application,” he explained.

To be eligible, the AICs meet seven criteria, including that they must be housed in a minimum-security facility, within four years of release, and cleared to go out on work crews outside of prison. In addition, all AICs must be cleared by medical and behavioral health services, have approval from their counselor and have a good conduct history from the institutions where they’ve been incarcerated. And, not surprisingly, they cannot be convicted of arson or sex offense crimes.

Prior to deployment, AICs receive training that is specific to their role. Fire suppression crews complete Firefighter Training (S-130) and Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior (S-190), and some AICs take Wildland Fire Chainsaws (S-212).

All AICs learn first aid and CPR, and those serving on camp or kitchen support crews must have a food handler safety card, all of which is included in the training provided by ODF. Cantlin said every AIC, regardless of crew assignment, must also be able to walk three miles with a 45-pound pack in under 45 minutes, just like any civilian wildland firefighter.

Civilian firefighters monitoring fire as it spreads toward a dozer line at the Double Creek fire on September 3, 2022. Photo by Payton Bruni.

Once they complete the training, according to a 2020 DOC Issue Brief, the AICs are certified in wildland firefighting, which can help them find jobs on civilian crews after release.

A maximum of 25 suppression crews of 10 people are contracted by ODF each year, Cantlin said, so as “not to interrupt other operations” that the AICs are responsible for in the facility. These other operations include typical prison jobs seen in movies and TV shows, like working in the library or on laundry or kitchen duty. According to a DOC Issue Brief, in October 2022, there were 13,197 total AICs actively held in prison. In 2020, researchers at the University of Oregon found there were 288 AICs deployed across 37 fires.

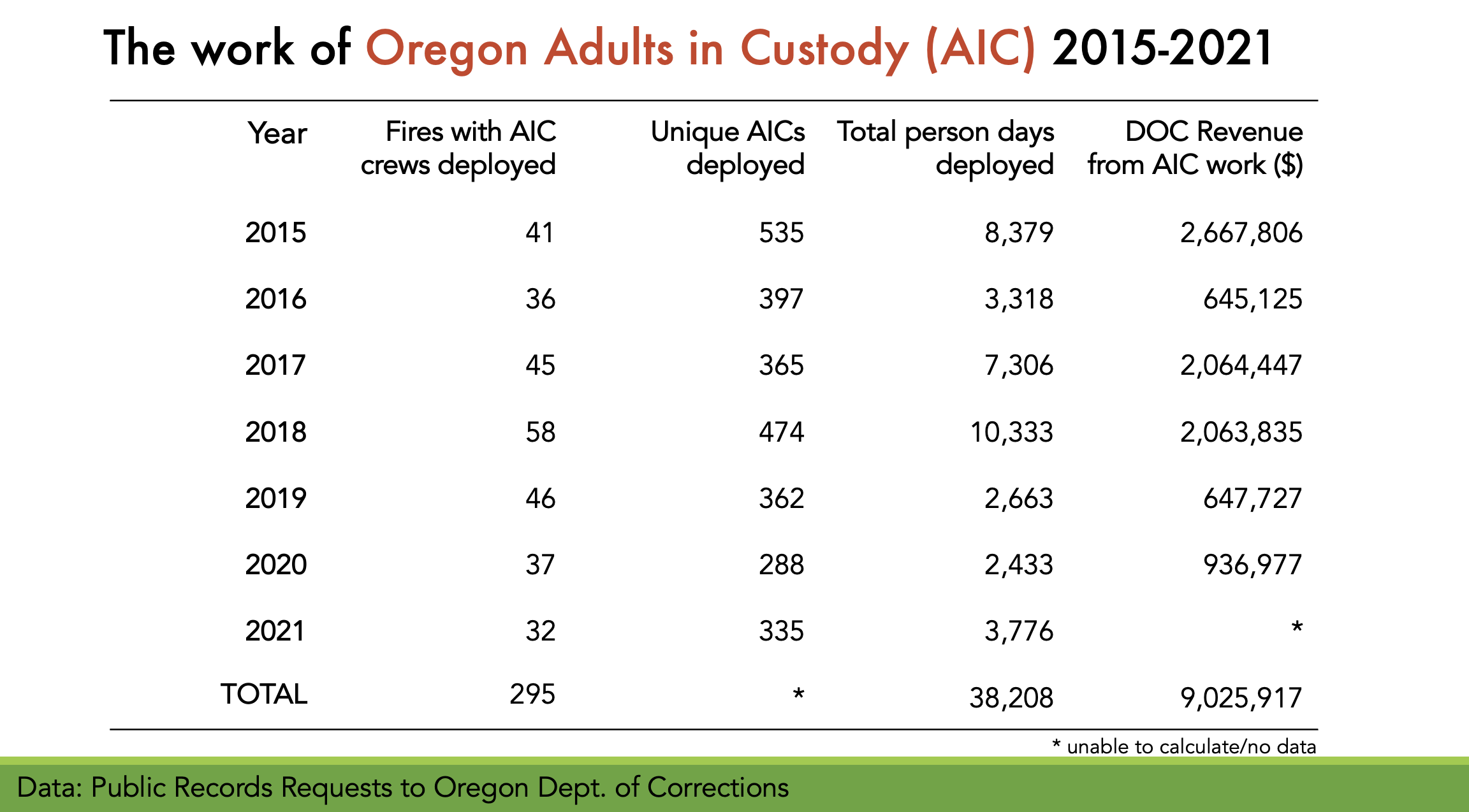

Chart and data provided by Leigh Johnson, a professor and researcher at the University of Oregon.

The AICs work up to two weeks on a fire at one time, with the possibility to extend to three weeks if their support is needed. After completing a deployment, AICs are required to take two days off when they return to the prison they are incarcerated. There, they can rest and contact family or friends, as they don’t have a way to communicate with anyone while they’re deployed to a fire.

In 2020, the Oregon DOC earned $936,977 from the work of AICs and correctional officers supervising the crews on wildland fires, according to data from public records requests compiled and evaluated by researchers with the University of Oregon.

How much are incarcerated wildland firefighters paid?

All AICs earn monetary awards, not wages. This distinction is important because their monetary award is not necessarily consistent, and they aren’t categorized as employees. They can earn from 4–18 points per day, depending on the work they are doing, said the DOC’s Communications Manager, Amber Campbell.

Performance Recognition and Awards System (PRAS) chart provided by Amber Campbell with the Oregon DOC.

At the end of each month, the daily points each AIC has earned are added up and then converted to a monetary award, 5% of which is held for a crime victims assistance fund. The points correlate to monetary awards ranging from $8 to $82 for the month, which becomes $7.60 to $77.90 after 5% is taken. Additionally, Gregg explained, 10% more may be deducted for the many AICs who need to pay court-ordered restitution, fees, or fines.

“Wildland fire crews are typically the highest point value assignments in the state,” said Cantlin. They earn 17 points per day while working on a fire.

Unlike some positions, the wildland firefighters receive supplementary compensation: the fire crew members are “given $6 per day on top of that as an additional award” from ODF, Cantlin said.

If an AIC firefighter works the maximum 22 days, then, they could be awarded up to $214 in a month, or $9.72 per day. AICs do not have any say in the hours they work or the fires they are sent to combat. ODF puts in a resource order with the DOC and then South Fork Camp dispatch evaluates which crew would be best to send and from which facility.

Is the program ethical?

Cantlin, McLay, and Campbell all continually emphasized that program engagement by AICs is voluntary. The AICs choose to apply, and they can withdraw at any time. Their training includes discussing the “inherent risks” that come with being out on a fire, McLay said. These risks include smoke inhalation, burns, impact injuries from falling debris, and mental health impacts.

Further, if they choose to withdraw, McLay says it’s no different than resigning from a normal job. “There’s no coercion and there [are] no repercussions if they don’t want to participate,” he explained.

“The AICs take a lot of pride in this program,” McLay continued. “We’ve got AICs that have done it three, four years and they really enjoy it because they’re giving back to the community. They’re part of something bigger than themselves.”

The sense of pride is a huge motivator and incentive for them, according to McLay.

For Gregg, the firefighting program is what drew him to South Fork Camp as he was moving from a medium- to minimum-security facility. He wanted to be out in the forest working for ODF, so once he transferred in 2018, he started working on a reforestation crew. He was able to complete the firefighting training that year, so in 2019 and 2020, he worked as a wildland firefighter, as well.

“Everyone wants to go to fires, and there’s a variety of reasons,” Gregg explained. “One of them is that when we’re out at fires, we get catered food. The type of food that we would get is — you know, I can’t even describe how much better it is than the food that you would get in prison. So that alone is a huge motivation.”

Furthermore, AICs enjoy a little more freedom while out on fires because they are in the custody of the ODF crew bosses in addition to their guards, and there is traveling involved to different parts of the state. Finally, the extra $6 per day is a big draw for AICs, Gregg confirmed.

“I mean, $6 a day sounds like a f — ing joke, but when you’re used to making a dollar a day,” he said, “that’s actually quite a bit of money.

“What I would say in contrast to all those great things about fighting fire is that the alternative is you sit in a cage.

“So, while it may sound voluntary because I really wanted to do it, I would say that in contrast to the alternative, it’s not really voluntary.”

Adam Gregg (back row, third from left) with his crew at the 2020 Echo Mountain fire in Otis.

While Gregg and DOC officials have opposing perspectives on the program’s voluntariness, they agree that the program gives AICs something to feel proud of.

“I saved people’s homes. I saved communities. I was, like, a hero — literally, a hero,” Gregg said, somewhat emotional even after two years. “And I’ve never had a job like that. I mean, a lot of people go their whole lives without having that feeling.”

What is the community impact?

Gregg said that while they normally do not interact with civilians who aren’t on fire crews, “the people that we encountered that were watching the flame come towards them — [those] people were not wondering what we were in prison for or if we were safe to be around.”

“Everyone was just grateful that we were there. People came back with signs and were honking their horns, going crazy. It was like being a rockstar.”

Leigh Johnson, Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Oregon whose research focuses on disasters and climate risk, worries that narratives about incarcerated labor often fail to recognize the true beneficiaries of AIC labor: the state and taxpayers, since incarcerated firefighters are much cheaper than civilian ones.

“I think this is one of the big messages of our project is all of the very ordinary and kind of day-to-day ways in which these prisoner crews are essential that go far beyond what we often think of around mega-fires,” Johnson explained.

Continuing, she said, “[AICs] get stuck with the really backbreaking mop-up work. So, [they are] absolutely essential. And at this point, given the way that the state approaches fire suppression, no, I don’t think we could do without them.”

Wildland fire engines lined up at the Double Creek fire on September 2, 2022. Photo by Payton Bruni.

A workforce we cannot do without

As climate change worsens and wildfires become more prevalent in new areas, Johnson expects the role of AIC crews to grow “increasingly significant.” Wildfires in Oregon are a smoky staple of the summertime, and researchers expect their devastating effects to continue. This may mean more experience for AICs to point to after release, but it may also mean more work for people who still earn less than Oregon’s minimum hourly wage for a full day’s work.

Measure 112 passed in Oregon’s November 2022 election, banning slavery or involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. This has called into question whether the required work programs that AICs complete as part of their incarceration, including the Wildland Fire Program, can — and should — be enforced at all, especially in their current form.

The Oregon State Sheriffs’ Association said in the 2022 Voter’s Pamphlet that Measure 112 “creates unintended consequences for Oregon Jails that will result in the elimination of all reformative programs and increased costs to local jail operations.”

Measure 112, the Sheriffs’ Association argued, may mean that costs could increase and the essential functioning of the jails and prisons could be impacted.

Arguments in favor of Measure 112 were made by a few county district attorneys, the ACLU of Oregon, the League of Women Voters of Oregon, the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, the Oregon Education Association, former Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski, multiple state senators and representatives, and more.

Their arguments were more moral in nature — versus the sheriffs’ economic argument — and focused on the modern-day values of Oregon citizens and rooted in moving toward justice for Black people after the harm caused by slavery loopholes through Jim Crow and mass incarceration.

While the Sheriffs’ Association claims operations could be halted, Johnson says that work “participation is voluntary insofar as you can choose whether you’d want to be on a fire crew or working in a laundry or a wood shop.

“So if you’re trying to choose between different options, you’re not forced to work the fire line, but you are forced to work. And that doesn’t change with the new measure that passed.”

However, Gregg worries that the measure might draw new scrutiny of the wildland fire program. Although there are ethical and logical concerns associated with the program, it has become integrated into Oregon’s ability to fight fires and it does provide benefits to AICs.

“My fear is that this will turn into a thing where they just stop doing it,” Gregg said about Measure 112, “because they don’t want to have to worry about paying people and they only want to do it if it’s slavery.”

Special thanks to Payton Bruni and Adam Gregg for sharing their photos in this article.

Originally published on Medium